Gender and collaboration in research

In Ductor, Goyal and Prummer (2018), we provide a systematic analysis of long-term trends in gender inequality in economic research. We use the EconLit database, a bibliography of 1,627 journals in economics compiled by the editors of the Journal of Economic Literature, over the period from 1970 to 2011.

First, over these four decades, economics has undergone a profound transformation. There has been a massive increase in the number of journals (from 252 in the period 1971-1975 to 1,260 in 2006-2010) as well as in the number of authors (from roughly 16,000 in 1971-1975 to 105,000 in the period 2006-2010).

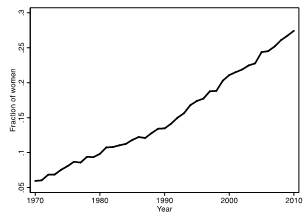

This increase has been accompanied by a significant change in the share of women in the profession: the fraction of female economists grew from 8% to 29% over the period we study (see Figure 1).

Remarkably, the increase in the share of women in the profession has not been associated with the disappearance of the gender output gap: after a fall up to 1990, the research output difference between men and women has remained essentially unchanged until 2011: men have produced 50% more output than women.

Indeed, there remain large differences in output even after controlling for experience and choice of field (and other observable factors).

Third, we turn to gender disparities in collaboration patterns among economists.

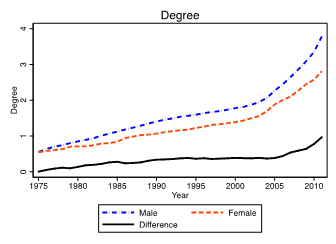

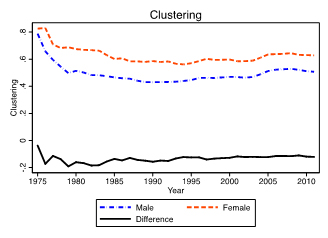

We identify large and persistent gender differences in networks: women tend to favour repeated interactions (stronger ties) and have a higher overlap among their collaborators (higher clustering), whereas men have more connections (a higher degree). Remarkably, despite the substantial increase in the number of women in economics, the differences in co-authorship patterns have either increased as in the case of degree (see Figure 2) or have remained stable as in case of clustering (see Figure 3).

Fourth, we investigate whether the difference in degree is mainly driven by homophily, defined as the desire of women to collaborate with other women, and for men to work with other men. Homophily and the underrepresentation of women in the profession may lead to disparities in the number of connections. This idea has been made precise by Currarini, Jackson and Pin (2009). Their model generates a positive correlation between the relative size of a group in the population and its (average) degree. We test their prediction in two ways.

We exploit variation in gender shares across time. Figure 2 illustrates that despite the increase in the number of women in the profession, the gender differences in the number of co-authors have actually increased. This holds true if we include various controls and is also robust if we consider cohorts instead of years.

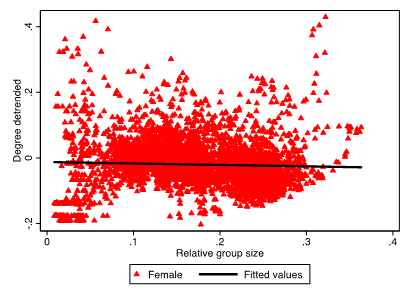

Next, we use variation in gender shares across fields. Some fields in economics, such as labour and development, have a larger share of women, whereas other fields, such as microeconomic theory have a smaller share of women. We show that the share of women in a given field does not have a significant impact on the number of co-authors that women have. This is illustrated in Figure 4.

So, we conclude that homophily is not a good explanation for the difference in the number of co-authors between men and women.

Fifth, the number of single-authored papers for women is lower and women tend to select more senior co-authors. Additionally, female co-authors tend to have lower past research output, both for male and female economists. This seems to indicate that female economists have no shortage of collaborators and manage to pursue projects with more productive economists. The fact that women are able to attract co-authors should hold especially for women with an established track record. In particular, the women, whose past output places them among the top economists should not have a shortage of potential collaborators. However, when considering the 5% most productive women, we see that the gender gap in the number of co-authors is larger than for less productive women.

Sixth, the variance in output is significantly greater for men compared with women. This may reflect differences in terms of risk taking, either due to different beliefs or different preferences, that is risk aversion. Alternatively, this may be due to systematic disadvantages that women experience in economics. Both explanations can match the stylised facts we describe:

Suppose men and women with similar ability decide on how to carry out a set of projects: whether to work alone or with others. If women face systematic disadvantages in terms of publishing (as evidenced by Hengel (2017)) that are difficult to overcome on their own, they will insure themselves through collaboration. Additionally, it is reasonable to suppose that – due to more flexible capacity and breadth of skills – the rewards to joint work are less uncertain than solo work: this suggests a negative correlation between risk-taking and share of research that is co-authored.

Both are consistent with our evidence: women write fewer single-authored papers.

Moreover, collaboration with senior co-authors may, and certainly can be perceived to be less risky than co-authoring with junior co-authors. A senior-co-author with more experience is likely to have a better sense of whether the idea is promising and how best to approach the work. In addition, there is less uncertainty about the ability and working ethos of senior scholars. If women face systematic disadvantages in economics, then a senior may also be better equipped to help overcome them.

So, disadvantages in the environment as well as lower risk-taking should be correlated with a higher fraction of senior co-authors – a prediction in line with our data.

Finally, we draw out the implications of differences in biases in the environment as well as risk-taking for network structure: someone who takes less risks would be more inclined to continue working with a known collaborator rather than to write a paper with a new unknown person. A lower inclination to take on risks will lead to a greater reliance on introductions through co-authors, leading to a greater overlap among co-authors. These patterns can also be explained by biases if un-collegial behaviour towards women is more acceptable, leading women to be more careful about their collaboration choices (these patterns are well documented by Ginther and Khan (2004)).

Taken together, therefore, disadvantages in the environment as well as differences in risk-taking, either due to differences in beliefs as well as in risk aversion offer a parsimonious explanation for the gender disparities in collaboration patterns we observe.

We also extend our study to sociology and the collaboration patterns prevalent there. Our results carry over qualitatively, with the exception of homophily, indicating once again, that there is little evidence for preferences of same-sex collaboration. However, the gender gaps both in output and collaboration patterns are quantitively smaller. This seems to be another indicator for a combination of risk taking as well as environmental factors that lead to the observed patterns.

Our study documents a gender output gap as well as gender disparities in co-authorship patterns. We rule out that homophily drives these results and offer an explanation for observed collaboration patterns, which hinges both on systematic biases against women as well differences in risk taking. This explanation is corroborated by our findings in sociology, where the same, but qualitatively smaller gender differences in collaboration patterns emerge.

References:

- Currarini, S, M O Jackson and P Pin (2009), “An economic model of friendship: Homophily, minorities, and segregation”, Econometrica 77(4): 1003-45.

- Ductor, L, S Goyal and A Prummer (2018), “Gender and collaboration”, Cambridge-INET Working Paper No. 1807.

- Ginther, DK and S Khan (2004): “Women in economics: moving up or falling off the academic career ladder?” Journal of Economic Perspectives, 18(3): 193-214.

- Hengel, E (2017), “Publishing while female: Are women held to higher standards?”,mimeo, University of Liverpool and VoxEU column.

- Mengel, F, J Sauermann and U Zolitz (2018), “Gender bias in teaching evaluations”, Journal of the European Economic Association.

- Sarsons H (2017), “Recognition for group work: Gender differences in academia”, American Economic Review: Papers and Proceedings 107(5) : 141-45.

- Wu, A H (2017) “Gender stereotyping in academia: Evidence from economics job market rumours forum”.

About the Author