Segregation and the Perception of the Minority

Cities can always become integrated if individuals bene fit enough from their interactions with members of the other racial groups.

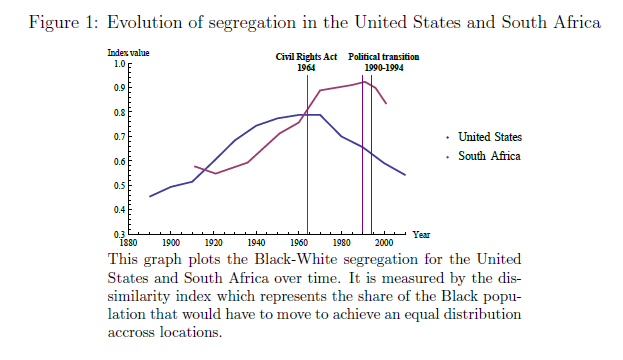

In 1971, Schelling [5] showed that a slight preference for living with individuals of your own group is enough to generate highly segregated cities. However, if we look at segregation over time in the United States, we see a rise from 1890 to 1970, mainly due to the enforcement of legal segregation, followed by a decline from this date onward [1]. In South Africa, we observe a similar pattern on a more recent period. Despite these patterns, previous researchers have still tried to explain the persistence of residential segregation, extending Schelling's result to the case of individuals having a strict preference for living in a completely integrated neighbourhood.

Nevertheless, they did not consider the gain (or the loss) that individuals may get from the interaction with a member of a different group. Moreover, whether the individual perceives this interaction as a gain or a loss might as well depend on whether the individual lives in the local minority or majority group. For instance, a person might not like Africans because he believes that they are violent, but he might like to listen to African music. Thus, as long as his taste for African music is strong enough, he might choose to live in a location that has some African musicians, then starting to build an integrated neighbourhood. But it might simply be that one group possesses the capital while the other constitutes the labour force. Then each group needs the other to be able to produce.

When we take this effect into account, it can overcome racism and homophily (i.e. preferences for their own kind) then ensuring the emergence of an integrated city. More precisely, we show that integration can always occur and persist in the long run no matter the preferences expressed by the two groups. In some circumstances, it might be necessary to implement a public policy of relocation to trigger effectively a transition to an integrated city.

We then study more in details three scenarios that we think of being the most relevant which we label “mutual reject", “White segregation versus Black integration", and “acting White". In the “mutual reject" case, both groups like their peers (homophily) and dislike the other group (racism). Some studies have found this situation representative of the relation between Afrikaaners and Africans in Modern South Africa [2]. If both groups perceive a loss from their interaction with the minority group, then for sure the city will evolve into a completely segregated configuration. This is the Schelling's result. On the contrary, if both groups perceive a gain from their interaction with the minority group, then whether the city will converge toward a completely segregated or integrated configuration depends on its history. If the racial mix of the city is initially unbalanced, then the city will end up segregated, and integrated otherwise. But if enough individuals move through a relocation policy, a government can trigger a transition toward an integrated city. If one group perceives a benefit while the other perceives a loss from their interaction with the minority, both segregation and integration can occur with and without public policies.

These different dynamics emerge because individuals face a trade-off between the different locations of the city which depends on their racial mix. In particular, the identity of the local minority in each location is essential for this trade-off as it is going to counterbalance or strengthen racism and homophily. Therefore, if the minority group values positively their association with the majority group, they will prefer to live in the location with the biggest minority even if they are the majority group in their initial location. On the other hand, if they perceive a loss from their interaction with the minority group, they will relocate to the location with the smallest minority. This trade-off changes with the racial mix of each location of the city, thus drives the location choices of the two groups, and therefore leads to segregation or integration.

In the "White segregation versus Black integration" scenario, one group (the Whites) expresses the same preferences as before, racism and homophily, while the other group (the Blacks) likes their peers, but now also appreciates the other group. Some studies found this kind of attitudes in the Detroit area in the late 1970s for Whites and Blacks [3]. As one group is more friendly to the other group, integration emerges more easily. As before, integration can emerge with a relocation policy if both groups perceive some benefit from their interaction with the minority, but now also if they perceive some losses. Moreover, integration without a relocation policy is also more easily achieved. Segregation occurs mainly when both groups perceive large losses when they interact with the minority group.

Finally, in the “Acting White" scenario, one group (the Whites) are still feeling racism and homophily, whereas the other group (the Blacks) does not want to live with their peers, and prefer living with the other group. This type of behavior describes the situation where Blacks reject the culture and habits of their group or the ghetto culture to embrace the practices of the dominant group like wearing suits, getting a college degree, having an interest in ballet [4]. In this situation, integration will occur for an even larger set of perceptions of the minority. But the novelty is that segregation will no longer be complete, there will always be some individuals of the minority group living with the majority group.

We then confront our model with South African data. We first seek if the perception of the minority is sizable compared to racism and homophily. Then we want to estimate in what kind of scenario South Africa is. For this purpose, we use the community profiles of the Post-Apartheid censuses conducted in 1996, 2001, and 2011 at the subplace level, which accounts for 2000 individuals in average. We exploit the asymmetric impact of the minority status in locations dominated by Blacks and in locations dominated by Whites to identify the preferences of both African and Whites. We can therefore recover the racism, the homophily, and the perception of the minority. We first find that the perception of the minority is actually quite strong. It represents between 116% and 456% the effect of racism and between 31% and 451% the effect of homophily from 1996 to 2011. Second, Blacks expresses racism and homophily, while it is less clear for Whites if they express racism, they have a strong preference for their own kind. However, with previous studies, we might support the "mutual reject" scenario. Finally, our two findings seem to indicate that South Africa should experience more integration since individuals are asking for more integrated neighbourhoods.

Our results have important policy implications for fighting segregation. Actual policies provide vouchers for the minority group in the private housing market of the more advantaged neighbourhoods as in London or in the Moving To Opportunity (MTO) experiment in the United States. However, this is actually done without knowing the underlying preferences of the individuals. Thus, individuals might move back to a disadvantaged neighbourhood, or affluent resident might move away turning it into a disadvantage neighbourhood after some time. So knowing the preferences of the individuals might help determining the on-going dynamics. Second, our results suggest that influencing preferences by public speeches or publicity campaigns might be as well another relevant policy tool against segregation. For instance, politicians might stress the benefit of the interaction between members of different groups. Finally, if we believe that a positive praise of the interaction between the different groups is the only acceptable public speech (it seems hard to advocate for a loss when interacting with members of the other group nowadays), then a policy mix of positive public speeches and a large-scale relocation policy is necessary for integration. To the best of our knowledge, there does not seem to be a country doing both type of policy together.

References

[1] David Austen-smith and Roland G. Fryer. An Economic Analysis of "Acting White ". Quarterly Journal of Economics, 120(2):551-583, 2005.

[2] David M. Cutler, Edward L. Glaeser, and Jacob L. Vigdor. The Rise and Decline of the American Ghetto. Journal of Political Economy, 107(3):455, Jun 1999.

[3] John Duckitt, Jane Callaghan, and Claire Wagner. Group identification and outgroup attitudes in four South African ethnic groups: a multidimensional approach. Personality & social psychology bulletin, 31(5):633-46, May 2005.

[4] Reynolds Farley, Howard Schuman, Suzanne Bianchi, Diane Colasanto, and Shirley Hatchett. “Chocolate city, vanilla suburbs: Will the trend toward racially separate communities continue?” Social Science Research, 7(4):319-344, Dec. 1978.

[5] Thomas C. Schelling. Dynamic Models of Segregation. Journal of Mathematical Sociology, 1(May):143-186, 1971.

About the Authors

Florent Dubois is a PhD candidate in Economics at the Aix-Marseille School of Economics and a research and teaching assistant at the Université du Maine. He obtained a bachelor degree from the University Toulouse I Capitole and a master degree from the Aix-Marseille University. He is actually conducting a thesis on the dynamics of residential segregation analysing both causes and consequences of this phenomenon.

Christophe Muller is a professor of economics and statistics at the Aix-Marseille University in France. He obtained a PhD in economics from EHESS, Delta in 1993 and Habilitation Diploma for Research Direction (HDR) from France (2008) and Canada (1994). Beyond development economics, his research interests include economic theory of welfare and household decisions (especially for anti-poverty and social policies), and econometric theory of quantile/robust regressions and survey design/analysis.